On this page:

Introduction

Safer Family Services (SFS) are designed to respond to families who are on the periphery of the statutory child protection system and whose children are at high risk of harm. The priority populations for the focus of SFS service provision are young parents under the age of 20 years, young mothers whose unborn children are the subject of notifications, adolescents with complex trauma and Aboriginal families with multiple and complex needs.

Common to all these families is the experience of trauma, either historically, in present day or both. Research shows that trauma has a powerful influence on child development. The adverse effects of trauma can manifest in a child’s behaviour, interpersonal relationships and mental health and if unaddressed, will often have negative effects across the lifespan and into subsequent generations (Trauma Informed Child Protection- Casey Family Programs). The presence of trauma is a driver of service need for CFSS (Trauma informed care in child/family welfare services Child Family Community Australia (aifs.gov.au)) and the management of the effects of this on staff, is crucial for the provision of quality services to families and in sustaining the CFSS workforce.

Purpose

An understanding of the prevalence of trauma and the potential adverse outcomes, has led to the Child and Family Support System adopting a Trauma Responsive System Framework (Government of South Australia, Department of Human Services, 2021, Trauma Responsive System Framework: A whole of system approach to building the capacity of the Child & Family Support System) as part of an organisation-wide, healing approach to working with families. There is growing recognition nationally and internationally of the need to move away from practices that unintentionally shame and humiliate clients, to one of valuing experiences and a process of enquiry into ‘what happened to you’ as opposed to ‘what is wrong with you?’ (Compassion Fatigue, Burnout and vicarious trauma. A Queensland Program of assistance to survivors of Torture & Trauma (QPASTT) Guidebook November 2016).

The purpose of this document is to outline the application of a trauma responsive framework, as it relates to the management of vicarious trauma in practitioners and staff across SFS (for more detail refer to the DHS Trauma Responsive System Framework).

It is acknowledged that staff who are not in direct service roles may also experience vicarious trauma. Staff in the Pathways Team, in MAPS, the Community Development Coordinators, Families Growing Together Team and in corporate roles may be exposed to traumatic client stories in the course of their work and have no direct knowledge of improved outcomes for families. This document is relevant for all staff, as well as managers and regional managers who are exposed to traumatic material in the course of their roles. This document does not extend to managing the vicarious trauma of clients and their families.

Prevalence of Trauma

The current literature on vicarious trauma is focussed on definitions, symptoms and associated factors. Information on prevalence is hard to find, but common to all findings is that child welfare workers in the course of their work have intimate exposure to significant histories of abuse, trauma and neglect and that greater exposure can lead to greater stress.

In South Australia demand on child protection and preventative services is increasing. In 2016 it was noted that one in three children are reported to the Department for Child Protection (DCP) before the age of 10 years (ibid). Common to these families is complexity related to domestic violence, substance use and abuse, financial hardship, unaddressed mental health issues, homelessness and unemployment.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Trauma experiences

For the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and similarly cultural groups that have collective experiences we see a higher prevalence of Trauma. In the Aboriginal community we see this directly related to the ongoing effects of intergenerational trauma from invasion and subsequent colonisation, forced removal and assimilation, (Stolen Generations) and discriminatory and exclusionary policies and practices. It is therefore important to understand the context of trauma experiences as systematically intending to erode the strengths of culture through the severing of connections to family, kinship systems, land, waters, language, parenting practices and identity to bring about the destruction of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society. Trauma has been done to Aboriginal peoples so needs to be front and centre of mind when drawing from a cultural lens.

Due to the systemic and systematic intent of these policies and practices the intergenerational trauma that is experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is collective rather than individual, crosses generations and incorporates the psychological as well as social aspects of historical oppression (Aguair, W., & Halseth, R., Aboriginal peoples and historic trauma: the processes of intergenerational transmission. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. University of Northern British Columbia.. Website accessed 29/11/2021). This is significant when considering the role of Aboriginal practitioners in SFS and the sense of cumulative trauma that may arise from lived experiences, with the combination of continued exposure to the trauma of Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal children, families, and community in the course of the work. This is referred to as ‘Blak burnout’ and encompasses experiences relating to micro-aggressions, racism, reduced sense of belonging, systemic barriers and feeling culturally unsafe in the workplace.

Blak Burnout also acknowledges not just experiences, but histories of carrying the pain of those ancestors that have come before. The epigenetic mechanism is known in community as blood trauma – where trauma is passed down altering the mechanism by which the gene is expressed. Blak burnout further acknowledges the collective load that Aboriginal peoples, (especially Aboriginal women) take on with family and community. Aboriginal employees can experience competing care, family, community, board and career obligations and an inability to undertake the role within regular office hours, due to the connections and expectations to and within community.

As a result of enforced trauma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples consistently score lower on the social determinants of health. Children are overrepresented in child protection statistics, with a 6 times greater likelihood of coming to the attention of child protective services and five times greater likelihood of being placed in out of home care, compared to non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (The Family Matters report 2017, Measuring trends to turn the tide on the over representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out of home care in Australia). Additionally, higher arrest rates, overrepresentation in prison populations and significantly higher rates of deaths in custody, are all attributed to intergenerational trauma (Australian Human Rights Commission: Indigenous deaths in custody. Website accessed 29/11/2021).

It is not only vital to understand the context of this collective experience and how it presents today, but also acknowledge individuals’ experiences of intergenerational trauma, intergenerational resilience, healing and the strength and protective factors of culture. The only way to start to heal and address Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s disparity in the social determinants of health and the prevalence of trauma, is through consistent culturally safe practices and culturally responsive and trauma informed approaches.

CALD Trauma experiences

For CALD practitioners and staff, trauma associated with migration, such as loss of country, culture, family and social roles can be compounded by pre migration experiences of war, torture and disaster as well trauma during transit (Perez- Foster 2001), upon arrival and in the process of re-settlement. This trauma can be cumulative and intergenerational and similarly, is to be considered in the context of vicarious trauma in the workforce.

Definitions

Vicarious Trauma

Vicarious trauma is an occupational challenge for those whose work exposes them to other people’s trauma and is considered a normal response to this exposure. It can be expressed across a range of physical, cognitive, behavioural, spiritual and emotional domains.

Vicarious trauma is defined as a “… transformation that occurs in the inner experience of the therapist (or other professional) that comes about as a result of empathic engagement with client’s trauma material” (I.Morrison, Z. (2007)."Feeling heavy": Vicarious trauma and other issues facing those who work in the sexual assault field (ACSSA Wrap No. 4. Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies).

The effects of trauma exposure in emergency workers was first identified in the 1970’s and subsequent research identified similar effects in nurses, emergency medical staff, allied health staff and crisis line workers. The term vicarious trauma was coined by McCann and Perlman in 1990 (McCann, I. L., Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatisation: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149) and has been subject to debate, with some stating that it is the product of countertransference, burnout and compassion fatigue. While much of the literature acknowledges the relationship between these concepts, vicarious trauma is considered unique and distinct. It involves a more enduring stress response, mirroring the effects of trauma and can manifest in a range of symptoms which are modulated by individual factors. Vicarious trauma is not a form of personal weakness but is a risk factor those who are working with and being exposed to cumulative trauma (ibid) or conversely, to a singular traumatic incident such as a death, an assault or serious accident.

Counter transference and secondary trauma

Countertransference is the emotional reaction of the practitioner to the client’s stories. The ability to understand the client situation as a result of empathising with them can be assisted by this connection, but also problematic in that it does not create a boundary for self-protection. Unless countertransference causes problems for the practitioner, they may not be aware this is occurring. In clinical practice, the role of supervision is integral here for exploring counter transference and other reactions caused by the work (Office for Victims of Crime, US Department of Justice- What is vicarious trauma? The Vicarious Trauma Toolkit. Ojp.gov). Refer to SFS Clinical Supervision Guide.

Secondary trauma is the process of relating to the event to the extent that the practitioner experiences the trauma symptoms. This is not confined to helping professions and can also be experienced by either a close family member or friend. Additionally, it is not related to repeat exposures and is not a cumulative response (Vistas Online ACA Knowledge centre Vicarious Trauma and its influence of self-efficacy- Terri Sartor).

Stress

Stress occurs in the workplace when work demands on individuals or teams exceed their ability to cope. Stress can be experienced in any role and is not specific to human service roles. Long term stress can lead to burnout if not addressed. The experience of stress can be alleviated by putting in place supports, work plans and boundaries. Symptoms of stress are synonymous with symptoms of compassion fatigue and burnout.

Interplay with compassion fatigue and burnout

Compassion fatigue and burnout are closely correlated with vicarious trauma but differ slightly. Compassion fatigue occurs as a result of longer term working with traumatised clients and families. It is empathic exhaustion, a wearing down of empathy and compassion resulting in a reduction of interest and capacity of the worker to empathise with clients and maintain an interest in their job (Louth, J. Mackay, T. Karpetis, G. & Goodwin-Smith, I. (2009) Understanding vicarious trauma: Exploring cumulative stress, fatigue and trauma in a frontline community services setting. The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia, Adelaide). Empathic engagement necessitates that the worker understand, be aware of and vicariously experience the world and perspective of another.

Symptoms of compassion fatigue relate closely to those of burnout in that it can manifest in withdrawal from job or personal connections, physical symptoms, sleep disorders, emotional lability and substance use or misuse (ibid).

Burnout is also connected with the effects of vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue- but can be experienced independently and more broadly across the helping sector because of high workloads, poor management and inadequate support, ongoing work stressors and physical/emotional exhaustion (ibid).

Burnout can present as job dissatisfaction, persistent exhaustion, cynicism, irritability and inefficacy. This can result in physical symptoms including fatigue, insomnia, as well as mood alterations and altered coping patterns such as substance misuse. In the workplace it can result in absenteeism and underperformance (Vicarious Trauma Office for Victims of Crime, US Department of Justice- What is vicarious trauma? The Vicarious Trauma Toolkit. Ojp.gov). Burnout does not result in a distortion of the view of the world, is preventable and can occur in any profession if workloads are felt to be unmanageable.

In practice, these do not exist in isolation of each other but can occur simultaneously and one can trigger the onset of another (Louth op cit 2009).

Impact of Vicarious Trauma

Vicarious trauma is a cumulative process induced by a continual and prolonged exposure to trauma stories, accounts and narratives and can have a negative effect on personal life and wellbeing. While individuals may respond to vicarious trauma in differing ways, a change in their worldview is inevitable from empathic engagement with the family’s trauma related experiences, memories and emotions (Quitangon op cit 2019). These changes may manifest behaviourally, cognitively and spiritually in both the personal and professional domains, as in the tables below.

Reference: Impact of vicarious trauma on personal functioning (Yassen, J. (1995). Preventing secondary traumatic stress disorder. In C.R. Figley (Ed.). Compassion fatigue: Secondary traumatic stress disorder from treating the traumatised (pp. 178–208). New York: Brunner/Maze)

Cognitive

- Reduced concentration

- Preoccupation with trauma

- Apathy

- Rigidity

- Reduced self esteem

- Self doubt

- Thoughts of self-harm

- Perfectionism

- Minimisation

Emotional

- Anxiety

- Guilt

- Numbness

- Fear

- Depression/

- Sadness

- Hypersensitivity

- Powerlessness

Behavioural

- Irritable

- Impatience

- Withdrawn

- Sleep disturbance

- Appetite changes

- Nightmares

- Elevated startle response

- Use of harmful coping- substance misuse

Spiritual

- Question life purpose

- Loss purpose

- Hopelessness

- Questioning religious beliefs

Interpersonal

- Decreased interest intimacy

- Mistrust

- Isolation

- Impact on parenting

- Self isolation

- Projection anger or blame

- Intolerance

- Loneliness

Physical

- Sweating

- Rapid heartbeat

- Somatic reactions

- Aches and pains

- Impaired immune system

- Dizziness

Impact of vicarious trauma on professional functioning (ibid)

Performance of tasks

- Decrease in quality/quantity

- Low motivation

- Avoidance of task

- Increased mistakes

- Perfectionist standards

- Obsessing on details

Morale

- Decreased confidence

- Loss interest

- Dissatisfaction

- Negative attitude

- Detachment

- Apathy

- Demoralisation

- Feelings of incompleteness

Interpersonal

- Withdrawal form colleagues

- Impatience

- Decrease in quality of relationships

- Poor communication

- Subsume own needs

- Staff conflicts

Behavioural

- Absenteeism

- Exhaustion

- Impaired judgement

- Irritability

- Irresponsibility

- Overwork

- Frequent job changes

Under or over-involvement with clients

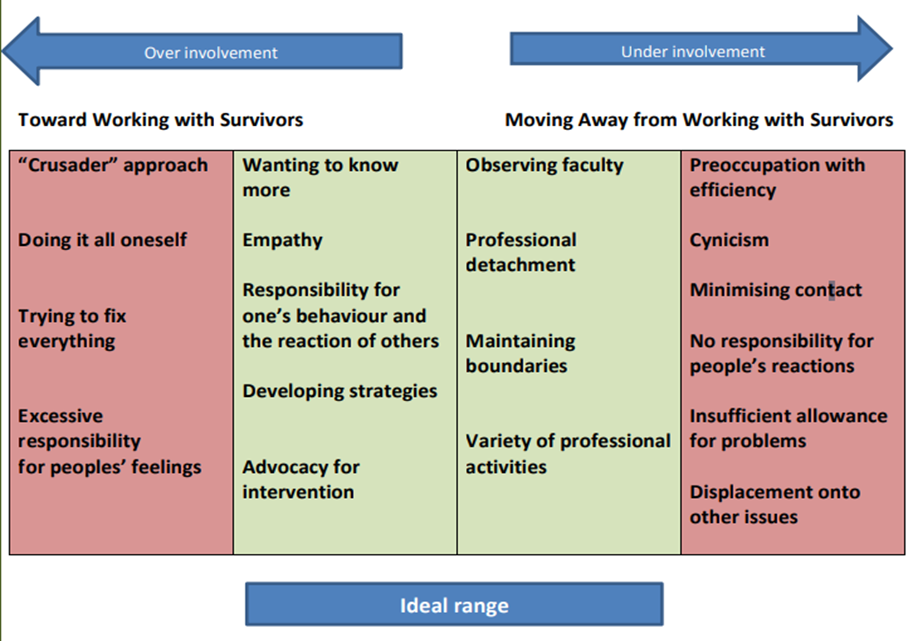

The following diagram demonstrates how these experiences of trauma and reduced professional functioning can impact upon work practices by either distancing from clients (under involvement) or becoming enmeshed, leading to over involvement (QPASST op cit 2016). While some movement across this continuum is considered to be normal and dependent on other domains of life, it is crucial to be aware of and understand the impact of this on self, work and behaviour. The optimal position is in the centre two columns (ibid).

Image taken from QPASTT Guidebook 2016 (ibid)

Text description of the graphic

The diagram shows how workers' experience of vicarious trauma and reduced professional functioning can affect work practices. Three areas are described: under involvement with survivors, over involvement, and the ideal range.

Under involvement may display in this way: workers may distance themselves from clients through preoccupation with efficiency, displays of cynicism, minimising contact with clients, taking no responsibility for people's actions, not allowing for problems, or displacement of concerns onto other issues.

Over involvement may display as a "crusader approach", attempting to do it all alone, trying to fix everything or taking excessive responsibility for people's feelings.

The ideal range of responses includes: observing faculty, professional detachment, maintaining boundaries, undertaking a variety of professional activities, wanting to know more about survivors, empathy, taking responsibility for own behaviour and the reaction of others, developing strategies and advocating for intervention.

Risk factors

Both personal and workplace related factors are implicated in the presence of vicarious trauma. Personal factors may include the worker having a history of trauma, pre-existing mental health conditions, less workplace experience or younger age, limited personal supports and/or interests and unhealthy coping systems.

The primary workplace risk factors are reported to be higher caseload allocations and relative inexperience of the worker, as well as the prevalence and accessibility of supports in the workplace (ibid). The literature shows that newer inexperienced workers are particularly vulnerable when working with traumatised clients. The quality and consistency of clinical supervision is paramount, as is access to specialised training around trauma (Louth op cit 2019), a supportive workplace that recognises vicarious trauma and integrates strategies to manage this aspect of the work.

Although the individual concepts of vicarious trauma are well understood, the effects of the combination of these factors across multiple experiences of adversity combined with individual characteristics and histories, are less clear.

COVID 19 and Vicarious Trauma

In March 2020, the Novel Corona Virus was declared a pandemic and strict measures of lockdowns, quarantining and social distancing were imposed worldwide. As a containment measure, workforces were instructed to work from home. The effects of enforced isolation, job losses, home schooling, changes in caring roles, increases in domestic violence, increased substance use and COVID mortality and morbidity rates (reaching saturation point through media outlets) have impacted greatly on communities, of which client families and practitioners are a part.

During COVID, the SFS workforce were considered an essential service and were providing services to families, while working either solely from home or in a mixed office/work from home mode. The speed at which this happened and the surrounding uncertainty, may have impacted upon a workers’ ability to manage vicarious trauma exposure.

At the time of writing this guide, COVID variants continue to cycle through communities worldwide and containment measures have been applied to manage the social, economic and health system burden.

In terms of managing health and safety and mitigating the effects of vicarious trauma, it is necessary to provide boundaries and monitor psychological wellbeing when working from home at these times. Strategies to do this are:

- keep to routines, have regular start and finish times and take breaks

- set boundaries and limit work to one area of the house

- maintain frequent and regular communication with manager/peers via phone, email and online platforms

- maintain a mixed mode of work where possible (time in office and time working remotely)

- disengage from work and log off at the end of the day

- take care of mental and physical health outside of work

- ensure the workstation is set up appropriately and comfortably

- comply with universal precautions as well as testing and reporting recommendations

- adhere to recommendations on vaccination schedules, unless otherwise contraindicated.

Vicarious Resilience

Vicarious resilience is defined as the positive impact on and personal growth of practitioners resulting from exposure to their client’s accounts and experiences of resilience. It is a relatively recent concept developed by Hernandez in 2007 (Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process (46 (2) 229-241). Remaining optimistic, seeing and celebrating changes and recognising achievements, contributes to vicarious resilience in the practitioner.

Vicarious resilience is only possible if implemented by both organisations and individuals, through the explicit encouragement and development of strategies to enable this. While there is a well-documented role for self-care (Quitangon, G. op cit 2019) this can fail to address the trauma felt upon returning to work and is only a partial view of building resiliency.

For SFS, the organisational focus on resiliency is through a well-developed understanding of the effects of trauma, the adoption of a Trauma Responsive System Framework for the delivery of services,clear policy and practice guidance around clinical and cultural supervision and the creation of a safe and open workplace culture. Leadership sustain staff by anticipating and responding to staff needs, showing appreciation and creating safe forums for communication (McFarlane, A.,& Bryant, R. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder in occupational settings: anticipating and managing the risk. Occupational Medicine-oxford, 57(6), 404-410) as well as utilising organisational and departmental resources to assist workers to address vicarious trauma, if it presents.

Open and transparent communication regarding organisational mission, strategy, resources and implementation of policies and procedures provides a strong foundation within the agency (Engage Victoria Framework for Trauma informed Practice- Department of Health engage.vic.gov.au/framework-trauma-informed-practice- website accessed 16/11/21). Providing staff with greater access to the organisation's strategic information, also lowers the level of vicarious trauma (McFarlane & Bryant op cit 2007).

For the individual, focussing on resilience and on what has been accomplished, can create a sense of purpose and a focus on strengths (Hernandez et al op cit 2007). The role of clinical supervision is integral here for talking openly about the challenges and successes of the work and the existence and promotion of vicarious resilience, in the face of dealing with trauma.

The practitioner’s personal distress and empathic responses if processed adequately, can result in growth for both client and practitioner (Pearlman & Caringi Pearlman, L. A., & Caringi, J. (2009). Living and working self-reflectively to address vicarious trauma. In C. A. Courtois & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide (pp. 202–224). The Guilford Press). The practitioner is encouraged to actively explore and become aware of their own reactions to the trauma stories they hear. The role of the individual is to live healthily with the experience. Vicarious resilience is fostered by a holistic approach and understood and actioned as outlined below.

Trauma Responsive Framework

A trauma responsive framework as articulated by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is a framework that promotes the physical, cultural and emotional safety of service users and staff. It is based on four R’s (SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014 SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for trauma informed approach. Rockville, MD pp9-10.):

- Realisation at all levels of an organisation or system about trauma and its impacts on individuals, families and communities

- Recognition of the signs of trauma

- Response- program, organisation or system responds by applying the principles of a trauma-informed approach

- Resist re-traumatisation of clients as well as staff.

These actions are applicable to all staff and are a warm, honest and effective way to deal with vicarious trauma in practitioners, leaders and other staff members.

A Trauma-Informed Approach

In a comprehensive co design process in 2019, CFSS canvassed the current literature, individuals with lived experience, workers who delivered services and those with cultural authority to design a Trauma Responsive System Framework (Government of South Australia, Department of Human Services, 2021, Trauma Responsive System Framework: A whole of system approach to building the capacity of the Child & Family Support System). This framework supports healing and avoids further traumatisation in the delivery of services to families and within the organisation itself. A trauma informed approach is most effective for addressing the high prevalence of trauma in client populations and avoiding compounding trauma though an unsafe response.

The principles of the Framework are:

- Trustworthiness- honesty and authentic ways of being that contribute to safety and trust. Sharing of information to support understanding of the system and honouring of safety and privacy

- Safety- focus on safe places and relationships over time to support healing

- Peer and Community Support- recognition of the importance of peers and communities for belonging, health, hopes recovery and healing

- Collaboration – Recognition of the need to collaborate, employ resources and draw upon the wisdom of families and communities to support healing and recovery. For those within CFSS and across the service system to walk together and share learnings.

- Empowerment and Self Determination- the creation of an organisation in which children and families have power and agency. Children and families are recognised as experts in their lives and their voices are promoted and listened to. A process of walking alongside families on their healing journey

- Knowing self and learning- Self-aware practitioners and leaders who are aware of and reflect on, personal bias, assumptions and own experiences of trauma and the impact of these on clients and communities. Celebrating diversity and strength and an approach of kindness, compassion and warmth toward children, families, peers and other organisations (Ibid- pp 10-11).

Trauma-Informed supervision

The trauma informed approach recognises that vicarious trauma may be an outcome of multiple exposures to traumatic material. Trauma informed supervision aims to provide supervisees with an opportunity to debrief, to recognise and respond to vicarious trauma and vicarious resilience and explore strategies which support communication practices, client work and organisational outcomes, while sustaining the practitioner (Blue Knot website - accessed 15/11/21).

Indicators of trauma informed clinical supervision (ibid)

- supervisors have knowledge of trauma and effects on children, families and communities

- supervisors have knowledge of the effects of vicarious trauma on practitioners and actively look for opportunities to recognise and discuss vicarious resilience

- creation of a safe learning environment

- clear boundaries and expectations around roles and processes

- a collaborative, supportive, reflective and reflexive process of sharing experience and expertise

- acknowledges good work practice and celebrates wins and good news stories

- considers professional goals and development

- is adaptable and flexible and allows for informal debriefing as required

Supervisors and regional managers will have access to a toolkit of vicarious trauma support resources, to utilise with their supervisees within supervision sessions. A supportive supervision environment can enhance the practitioner’s ability to acknowledge, express and work through experiences of vicarious trauma and these tools are designed to assist in this process, as well as facilitate conversations around work satisfaction and vicarious resilience.

In a trauma informed organisation, the responsibilities of staff at all levels, are outlined below.

Practitioners are responsible for (ibid)

- utilising supervision and debriefing for support

- knowledge of vicarious trauma and the effects on workers

- quality of practice and seeking guidance and knowledge appropriately

- attending work related training and engaging in professional development activities and processes

- contributing to and participating in a positive and culturally safe workplace culture

- implementing processes to monitor/manage well being when directed to work from home and adhering to OHS requirements

- taking regular breaks and lunch breaks

- accessing annual leave

- creating effective recreational and self-care activities and monitoring own wellbeing and safety

- raising workplace issues with supervisors (see appendices for a range of tools to monitor and manage mental health and wellbeing)

- utilising EAP if required

- awareness of resources on DHS Wellbeing and Psychological Health intranet page (DHS workers only)

If staff find that utilising the existing frameworks to manage vicarious trauma is inadequate for them, EAP is able to offer workplace funded, professional counselling services. Speak with a manager if requiring details or utilise DHS intranet links to find out more.

Supervisors and Managers are responsible for

- the provision of trauma informed clinical supervision

- provision of culturally safe supervision

- knowledge of vicarious trauma and the effects on client and client families

- knowledge of vicarious trauma on supervisees

- understanding and raising the profile of vicarious resilience

- promoting and modelling an organisational culture that is trauma informed

- monitoring supervisees workloads and wellbeing

- supporting training and professional development

- supporting staff to seek external supports, where required

- escalating matters and advocating for resources where required

- awareness of resources on DHS Wellbeing and Psychological Health intranet page (DHS workers only)

Senior staff are responsible for (Kourt, S. P., & Green, S. A., Trauma informed organisational change manual. School of Social Work, University at Buffalo 2019)

- the resourcing of trauma informed supervision and debriefing

- promoting an organisational culture which acknowledges, educates on and normalises vicarious trauma and raises vicarious trauma awareness.

- adopts trauma informed frameworks and commits resources to support implementation

- fosters and cultivates an organisational culture of care, cultural safety and respect

- ensuring manageable workloads through the provision of:

- caseload diversification and opportunities to diversify roles- where relevant and if required

- adequate resources to do the work- physical resources such as cars, technology and staffing.

- administrative processes to support the work

- training, skills and knowledge- adequate provision of workforce development and training

- availability of policy and practice guides and clinical resources to supplement training and clinical supervision

- flexible work practices

- collaboration- employees, service users and those with lived experience are encouraged to provide input into policies and system design

- mutual understandings of trauma and trauma informed approaches across CFSS

- ongoing evaluation, organisational improvement- commitment to data collection across organisation and integrating into practice and policy.

Bibliography

Aguair, W., & Halseth, R., Aboriginal peoples and historic trauma: the processes of intergenerational transmission. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. University of Northern British Columbia. Https://www.ncah-ccnsa.ca/34/. Website accessed 29/11/2021

Australian Human Rights Commission: Indigenous deaths in custody. https://humanrights.gov.au/Indigenous-deaths-custody Website accessed 29/11/2021

Blue Knot https://professionals.blueknot.org.au/supervision-and-practice- website accessed 15/11/21

Casey Family Programs Trauma Informed Child Protection- https://www.casey.org/why-become-trauma-informed - website accessed 8/11/2021

Compassion Fatigue, Burnout and vicarious trauma. A Queensland Program of assistance to survivors of

Engage Victoria Framework for Trauma informed Practice- Department of Health https://engage.vic.gov.au/framework-trauma-informed-practice- website accessed 16/11/2021

Government of South Australia, Department of Human Services, 2021, Trauma Responsive System Framework: A whole of system approach to building the capacity of the Child & Family Support System

Government of South Australia, Department of Human Services, 2021-2023, Roadmap for reforming the Child and Family Support System

Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process, 46 (2) 229-241

Kourt, S. P., & Green, S. A., 2019, Trauma informed organisational change manual. School of Social Work, University at Buffalo

Louth, J. Mackay, T. Karpetis, G. & Goodwin-Smith, I. (2009) Understanding vicarious trauma: Exploring cumulative stress, fatigue and trauma in a frontline community services setting. The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia, Adelaide

McCann, I. L., Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatisation: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149.

McFarlane, A.,& Bryant, R. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder in occupational settings: anticipating and managing the risk. Occupational Medicine-oxford, 57(6), 404-410

Morrison, Z. (2007)."Feeling heavy": Vicarious trauma and other issues facing those who work in the sexual assault field (ACSSA Wrap No. 4. Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

November 2016 Trauma informed care in child/family welfare services Child Family Community Australia (aifs.gov.au)

Office for Victims of Crime, US Department of Justice- What is vicarious trauma? The Vicarious Trauma Toolkit. Ojp.gov

Pearlman & Caringi Pearlman, L. A., & Caringi, J. (2009). Living and working self-reflectively to address vicarious trauma. In C. A. Courtois & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide (pp. 202–224). The Guilford Press

Perez-Foster R, M,. 2001, When immigration is trauma: Guidelines for the individual and family clinician. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71 (2).

Quitangon, G. MD. 2019 Vicarious Trauma in clinicians: Fostering resilience and preventing burnout, Psychiatric Times, Vol 36, Issue 7 Vistas Online ACA Knowledge centre Vicarious Trauma and its influence of self-efficacy- Terri Sartor

SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014 SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for trauma informed approach. Rockville, MD pp9-10Torture & Trauma (QPASTT) Guidebook

The Family Matters report 2017, Measuring trends to turn the tide on the over representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out of home care in Australia

Yassen, J. (1995). Preventing secondary traumatic stress disorder. In C.R. Figley (Ed.). Compassion fatigue: Secondary traumatic stress disorder from treating the traumatised (pp. 178–208). New York: Br