Download print version:

On this page:

Acknowledgement

We in Safer Family Services (SFS) acknowledge and respect Aboriginal people as the first people of this country and recognise the traditional custodians of the lands in South Australia, the lands on which we practice.

We acknowledge that the cultural, spiritual, social, economic, and parenting practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people come from traditional lands, waters and skies, and that the cultural and heritage beliefs, languages and lore are still living and of great importance today.

We acknowledge Elders past, present and those emerging, which of course is the children. We further acknowledge Aboriginal staff, families and community working to keep children safe in the protective strengths of culture, with a strong sense of self and identity.

We are committed to voice and truth telling, ensuring that the needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are incorporated in the design, development, monitoring and evaluation of deliverable actions.

Statement of Inclusion

SFS acknowledges and respects the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNHRC 1989) and upholds children’s rights by placing them at the centre of our work. At all times in the delivery of services, SFS will seek to advocate for a just and inclusive society that values and respects a child’s identity and voice, within the context of their family, culture and community.

SFS staff and leaders create, model and promote a workplace culture where differences, lived experience, culture, gender identities, sexualities, faiths, ethnicities and abilities are respected and valued, and their voices elevated. We recognise the contributions these communities make and are committed to working alongside them in partnership. SFS will address individual and systemic issues by tackling barriers or highlighting service gaps that prevent children from living safely with their families.

Allyship accountability

All SFS staff are called to commit to developing their allyship and to respect the diversity of all individuals. This lifelong process or journey is known as allyship and is one of learning, understanding and building meaningful relationships based on trust and accountability with marginalised individuals and/or groups of people. Allyship accountability is about being proactive in reflecting on and addressing internal biases and being receptive to feedback and responsible for one’s actions, free from defensiveness or ignorance. Advocacy and allyship are deeply related. Advocacy is how allyship is integrated into our work by driving change in our roles and across organisations and sectors (Say It Out Loud).

Note: The term Aboriginal is used throughout this document and is respectfully inclusive of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Practitioners should include in their work all the children in the family, including unborn children. References to children and/or young people refers to children antenatally and individuals up to the age of 18.

Purpose

The purpose of this practice guide is to provide practitioners with practical steps in the identification of cumulative harm, through a considered process of assessment and analysis. By identifying the multiple stressors and adverse experiences that contribute to cumulative harm, practitioners can respond with tailored interventions, through the case management process. The guide outlines:

- Current understandings of child abuse and maltreatment

- The definition of cumulative harm

- The impact of cumulative harm on children and young people

- Assessing and analysing information

- Responding to cumulative harm.

Child abuse or child maltreatment

Child abuse and child maltreatment are terms used interchangeably in the literature. Both refer to abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age and include all types of physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse as well as neglect, negligence and exploitation which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development, or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power (World Health Organisation 2022).

What is cumulative harm?

Cumulative harm describes the negative impacts of exposure to long-term abuse and neglect during childhood which leads to the child's decreased sense of safety, wellbeing, and stability. A child’s need for adequate nutrition, supervision, medical attention, educational, developmental, or emotional nurturance may be neglected and they may not have access to basic cleanliness and safe living arrangements (ACT Government 2019). Their physical, sexual, or emotional safety may be compromised. Research shows that most children who are maltreated are exposed to multiple forms of abuse and childhood adversity (ibid).

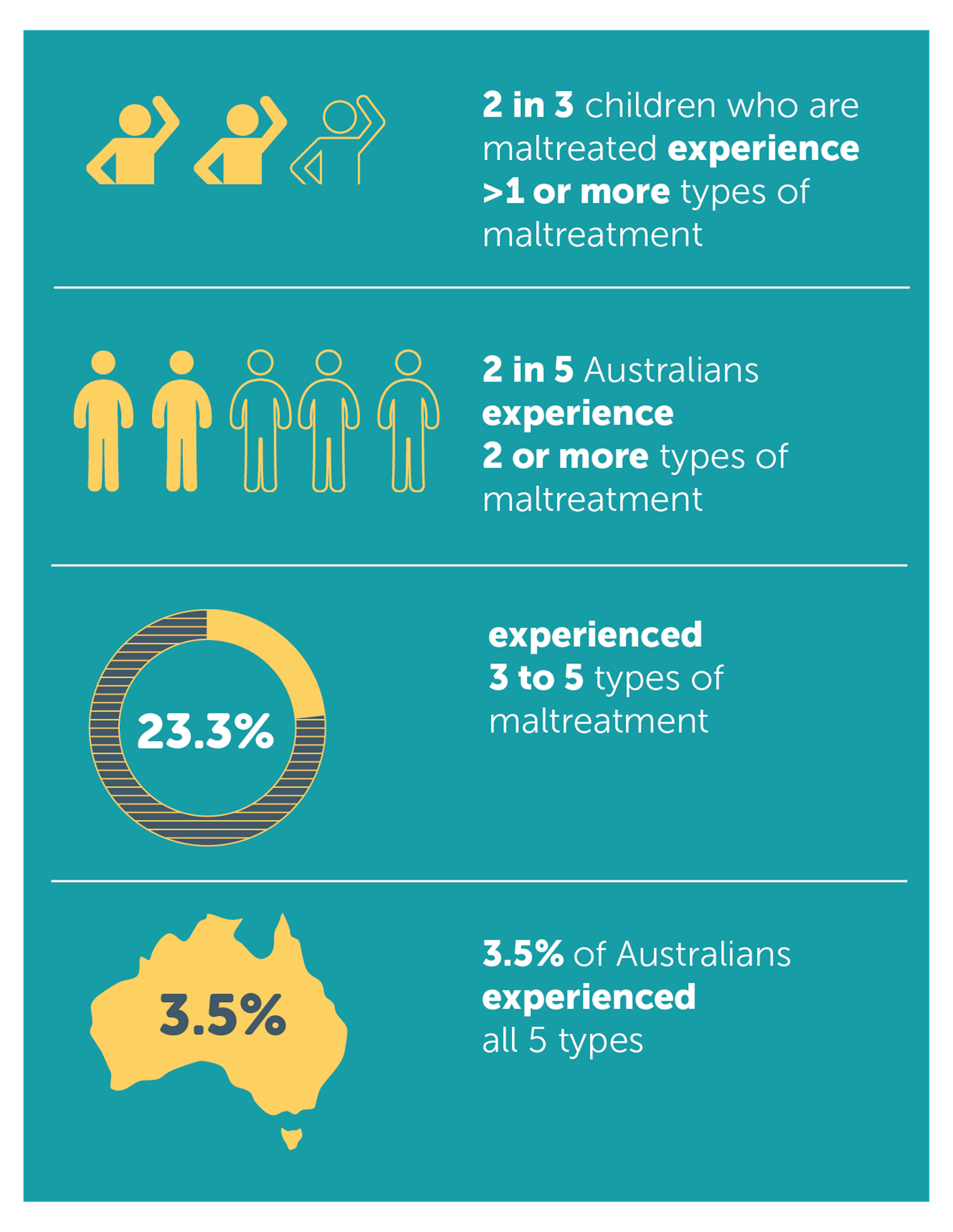

Data from The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS 2023) which looked at all forms of child maltreatment at a national level found that single type maltreatment was reported by 22.8% of respondents, whereas multi-type maltreatment was reported by 39.6% of respondents and exposure to domestic violence was the most common individual maltreatment type. A further 3.5% reported having experienced all five maltreatment types.

Image: Mathews Bet al. (2023) The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: findings from a national survey. Med J Aust. 218 (6). Is found on home page: The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS)

Image: Higgins DJ, et al. (2023). The prevalence and nature of multi-type child maltreatment in Australia. Med J Aust. 218 (6). Is found on infographic Prevalence of multi-type maltreatment across the Australian population - The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS)

The effects of chronic abuse and neglect are gradual and there are usually no specific events to trigger an intervention or system response. This is different from physical or sexual abuse, where there are usually clear incidents identified and observable injuries that are likely to trigger a notification and response (Bryce 2018).

The Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017

The South Australian Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017, Section 18(3) states that: ‘In assessing whether there is a likelihood that a child or young person will suffer harm, regard must be had to not only the current circumstances of their care but also the history of their care and the likely cumulative effect on the child or young person of that history.’

While the construct of cumulative harm is incorporated into child protection practice and legislation in South Australia, system responses remain largely incident focussed. A practice response that places cumulative harm and recurrent maltreatment on par with episodic maltreatment is actively evolving. Event driven models result in children and young people experiencing cumulative harm rarely meeting thresholds for statutory intervention (Bryce 2018).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families

The impact of historical colonisation and ongoing dispossession, oppression, racism and unresolved grief and intergenerational trauma have undermined the social and cultural structures of Aboriginal communities. This has led to heightened rates of child abuse and neglect in Aboriginal communities and an over representation of Aboriginal children in the child protection system across Australia (AIFS 2020).

The relative social, political, economic and cultural disadvantage experienced by many Aboriginal families and communities, places them at increased risk of cumulative harm, due to exposure to traumatic life events such as illness, family violence and financial stress (ibid). Additionally, differing approaches to child rearing may lead to increased scrutiny due to unconscious bias and a lack of understanding by mainstream providers, regarding the role of extended family and community in Aboriginal culture, in terms of parenting and supporting parents.

Practitioners should remain open minded and curious in relation to child rearing practices and should actively interrogate their own unconscious bias. Consider strength of culture and protective factors when working with Aboriginal families and utilise cultural consultation to promote working in a holistic way that is healing and avoids re-traumatisation.

Culturally and linguistically diverse children and families

Refugee and migrant families may be dealing with traumas because of their experience of war, oppression and/or dislocation. They are often making significant adjustments to a new culture and different way of life, while managing unresolved trauma and loss. This places additional stress on families and increases children’s vulnerability (ACT Government 2019).

Impact of cumulative harm on children

Gaining the necessary skills to manage stress is an important part of a child's development. The evolutionary response to danger is an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and hormones such as cortisol. When children are consistently in supportive environments with nurturing adults, they have generally learned the skills to regulate their physical reactions which results in stress-induced changes returning to normal after the event. This leads to the formation of healthy stress management systems (ACT Government 2019).

When children experience long-term trauma or distress without the help of trusted adults, the response to danger is intense and persistent and the child has nobody to help them regulate. Chronic abuse, neglect and trauma trigger a prolonged activation of stress management systems which can interfere with a child's neurological development, impair their ability to process sensory, emotional, and cognitive information and lead to delays or disorders in their development (Bryce, Collier 2022) .

A single traumatic episode can result in behavioural responses when there are reminders of that trauma, whereas chronic trauma can have far reaching and pervasive effects on children’s development which may not be immediately obvious but can become more visible as the child grows older and can adversely affect functioning in adult life. Research shows a strong predictive relationship between cumulative harm and the probability of poor physical, emotional, mental, and social health outcomes across the lifespan (AIFS 2014) .

Practice strategies

When practitioners undertake a thorough assessment for cumulative harm, they are focussing on the presence and impact of ongoing harmful conditions, circumstances, or incidents, while keeping the child’s experience at the centre. Consideration is given to strengths and protective factors, and the protections afforded by family, kinship and community. This means establishing a clear picture of each child’s experiences, and in partnership with parents and family, developing a rich understanding of the child’s past and current experiences (ACT Government 2019). Practitioners continue to add to and update information as the work with the family progresses.

Practice note:

Risk can escalate rapidly and unpredictably. Assessing for risk is not a one-time occurrence or a periodic undertaking but a task the practitioner undertakes on a continuous basis, during and after each contact with the family.

Risk related to family and domestic violence will be referenced but not covered in this guide, due to the extensive nature of topic and the considerations required for practice.

Evidence and information gathering

Practitioners seek, share, sort and store information in order to build a picture of the child within the context of their family, culture and community. This process encourages practitioners to analyse and understand what the information held at a point in team means for the child or young person. When information is believed on reasonable grounds to be accurate, valid and reliable, then it can be considered as evidence (Victoria Government 2021).

The process of seeking, sharing, sorting and storing information has been adapted from a section of the Victorian Government’s SAFER children framework guide (ibid).

SEEK information and evidence

View the case history

Practitioners should explore the context of the concern regarding the child's history and any previous reports, notifications, or information on file. Consider the impact on all the children in the home, including unborn children, when information gathering and assessing.

Previous reports or notifications that did not meet thresholds for intervention or were not substantiated, can provide critical information and inform assessments that are sensitive to the possibility of cumulative harm (Victoria Government 2012). Practitioners should investigate:

- All reports of abuse or neglect

- Multiple sources alleging similar issues

- Multiple similar events of an apparent lesser impact

- Whether the allegations have escalated in type or number

- Reports from teachers, health professionals, housing associations, government and non-government agencies

- Referrals made to services

- The history of engagement and outcomes from previous interventions.

Reports of unborn child at risk due to:

- Lack of antenatal care

- History of DFV

- Substance use during pregnancy

- Expectant parent with a history of self-harm/suicidal ideation

- History of parental criminal activity

- Issues with access to/low visibility of child.

Practitioners should look for:

- Family complexity (mental health, substance misuse, DFV, disability, medical issues)

- Neglect of medical needs/appointments

- Child not meeting developmental milestones

- Evidence of neglect/chronic neglect

- Issues of squalor and/or hoarding

- Reports against other siblings in the family

- Allegations of harsh or excessive discipline in public

- Financial and housing insecurity

- Social isolation and/or limited informal or formal support

- Parental history of trauma/child protection involvement.

Allocation meeting

An allocation meeting occurs with the case team after a referral is received and before any initial engagement with a family. This supports both worker safety and quality service delivery from the very first contact.

The allocation meeting should occur promptly after a referral is received, ideally within 1 to 2 working days, and involve the allocated worker, supervisor and senior practitioner at a minimum. Aboriginal Cultural Consultants and other relevant staff may be included as available and/or needed. The supervisor is responsible for case noting a record on C3MS to summarise key discussion points and actions from the allocation meeting.

The four dimensions of analysis that guide the assessment for the likelihood of cumulative harm is a useful way to help analyse the information that is available at the point of referral, and to understand what it may suggest, as well as to identify gaps or unknowns. This process supports practitioners in being able to actively seek out the information that may be required from other services and to enter early engagement with curiosity and informed questions.

Initial home visit

The task in the initial visit is to secure connection with the family and ideally, access to the home. Families may have fears that their children will be removed and may view practitioners as a part of the statutory system. This may lead to an avoidance of engagement. Refer to the SFS Assertive Engagement Practice Guide and always work in ways that are trauma informed.

Squalor and hoarding

In instances where children and young people are experiencing chronic and severe neglect and where conditions of squalor exist, families may be reluctant to engage (Government of South Australia CDSIRC 2022). Assertive engagement strategies are crucial to ensure the safety of children.

Squalor and hoarding are addressed here to ensure the fullness of the assessment process (working with squalor and neglect will be explored in greater detail in subsequent practice guidance).

The presence of squalor is to be considered a ‘red flag’ that children and young people are in grave danger of serious harm (ibid).

The Child Death and Serious Injury Review Committee (2022) in a review of 13 cases of child deaths found that squalor was an identifiable factor in these deaths and that child mortality often occurs in the context of chronic neglect and cumulative harm. The Committee stated that squalor presents significant hazards to children and young people and is an indicator of limited parenting capacity and chronic neglect (ibid).

Risk assessment tools have been developed to assist with assessing domestic squalor. For instruction on managing squalor and hoarding as well as reference to the use of assessment tools, see SA Health A Foot in The Door.

The Severe Domestic Squalor Assessment Scale (SDSAS) provides a framework for the identification of individual areas of concern within the home and can support referrals to partner agencies.

Where there is compulsive hoarding rather than severe domestic squalor, practitioners may prefer to use hoarding-based assessment tools such as the Clutter Image Rating Scale(Frost et all 2008).

Worker safety

When practitioners approach homes where squalor is reported, they should take note of the exterior and surrounds of the home. Upon entering, practitioners may find that:

- the home has a strong or unpleasant odour

- there is excessive rubbish and extreme lack of cleanliness

- there may not be anywhere to sit or move around with poor lighting and ventilation

- there may be hoarding of animals with animal faeces on floors.

Practitioners should:

- carry gloves, hand sanitiser, mask and gowns, and wear as required

- wear closed shoes, covered clothing and limit workbags. Avoid placing items on the floor/carpet

- be mindful of where to sit. Preference hard kitchen chairs over fabric lounge chairs or cushions, or elect to stand.

Environmental risk

When entering a home practitioners may need to explain to clients why they are donning a mask and gloves. Offer sensitive but honest explanations such as: “Please excuse me, but I’m going to wear a mask and gloves. It is important that I protect myself because I am sensitive to animal/pet hair/dust/smoke. I hope you’ll understand” (Eppingstall 2023).

Practitioners should ask to see the whole of the house, especially children’s rooms and sleeping arrangements. Record any environmental risks (Catholic Health Care 2021).

- Look for smoke detectors and open flames or ovens used as a heat source. Check for clearance around combustible stoves.

- Note if power points are overloaded or there are exposed wires.

- Safe pathways — these are continuous pathways through house and allow easy entry and exit. Check that all doors open to 90 degrees and windows are unobstructed.

- Structural integrity — floors and stairs appear stable, no leaks in roof, no water damage or mould.

- Evidence of insects or vermin infestation, human or animal waste, mouldy or rotten food.

- Working toilet and shower, sink, washing machine and fridge.

- Accessible and adequate furniture (bedroom/ bed and clean and hygienic bedding).

- Functioning and accessible kitchen areas.

- Safe sleeping areas for babies.

- Working utilities.

Engaging with families

Practitioners engage compassionately and respectfully with families, with an awareness of the importance of relationship-based practice. Be upfront about the practitioner role, reasons for involvement and limitations to privacy and confidentiality. Work towards building trust to allow for exploration of difficult areas and support partnering with families for change.

Talk with the parents

Practitioners should (ACT Government 2019):

- Have conversations with the parents about the concerns and seek their understanding of the situation

- Keep the focus on the child’s needs

- Orient parents towards a child focussed lens by explaining how the neglect is impacting upon on their child’s development

- pay attention to the cumulative stressors in the parents’ lives without colluding with the behaviour.

Additionally, practitioners should consider:

- The family’s strengths

- Protective factors

- Any characteristics of the child that make it harder to parent and meet the child’s needs (disability, complex medical issues such as PEG feeding, or behavioural characteristics)

- The parents’ beliefs/understandings of their child’s needs

- Information related to culture and how this builds on safety for the child

- How the family has tried to manage issues before your involvement and the outcome

- Exceptions/time that the problem behaviours have not occurred or been repeated and what was different at these times (ibid).

Talk with and observe the child/ren

Child centred practice requires meaningful engagement with the child or children. Through observation, gentle conversation, deep listening and taking the child’s perspective into account, practitioners gain informed insights into their circumstances and how the current situation is affecting them.

Interacting with children

Practitioners should adapt their communication style to the child's developmental age. Providing clear and developmentally appropriate explanations of their role and what will happen in the session (to the level appropriate) assists practitioners to engage with children, build trust, encourage involvement, and can lessen their anxiety (Hervatin 2020).

Practitioners should also maintain an awareness of how their body language, positioning tone of voice, facial expressions, gestures and eye contact may potentially impact on children.

Communicating with children

Paying attention to a child’s non-verbal cues such as body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice can offer useful insights into a child’s views. Carefully attending to a child’s non-verbal clues can allow practitioners to respond in ways that convey safety and support and encourage engagement. For example, a child’s hushed voice and reduced eye contact can signify that the child may be anxious, fearful or shy and would benefit from additional time and gentle encouragement to engage (ibid).

When relating to children, it is helpful to create an environment that allows them to feel comfortable, safe and respected. By using a favourite book, toy or interest, the practitioner can establish a foundation for communication and understanding. This shared interest serves as a bridge between the practitioner and the child, allowing them to start to formulate a connection.

Pay attention to the child's level of development in terms of how they play, communicate, and how they seek comfort when they are upset. Take note of how they interact with their parents and respond to you and if they are verbal, how they express their emotions.

The same observations should be done with children or infants who are pre-verbal or non-verbal. Additionally, practitioners observe the child’s physical wellbeing, as outlined below:

- What is the impact of any squalor and hoarding on the child or children?

- How does the child present? Engaged? Withdrawn and listless?

- Are they meeting developmental milestones for play and communication?

- Do they display comfort seeking behaviour if distressed?

- Are there toys in the house and if so, what toys are used in play and how are they used?

- What is the quality of the parent/child relationship?

- What is the child’s relationship with siblings? Extended family?

- How does the child interact with other children?

If the child is verbal:

- Ask about their day, their routines. What happens after school?

- Ask about their home and family life. Who lives in the house? Who visits? Who looks after them?

- What makes them happy? Sad?

- What is the child saying and not saying and what might this tell you? (ibid).

Making observations

Direct observation is crucial to when gathering information. It assists in building a picture of the child’s experience. It allows for the voice of the child to be included, even if they cannot verbalise due to immaturity or disability.

When making your observations consider:

- The child’s age and increased vulnerability of newborns

- The child’s developmental level, relative to risk factors

- Knowledge of child development, trauma and attachment.

Observe the following:

Physical wellbeing

- Are the child’s basic needs being met? Appropriate space and sleeping conditions (safe bedding and sleeping and infant positioning practices)

- If the child is crawling, how are they negotiating the home?

- Are their nutritional needs being met? Do they have adequate and appropriate clothing?

- Are medical/allied health needs attended to including ante-natal appointments?

- How does the child present? Note their personal hygiene/cleanliness/alertness

- Does the child appear pale, underweight for age, sunken eyes, malnourished?

- Are there signs of bruising? Injuries? Dental decay? Infection? Head lice? Skin conditions?

- How is the child spending their time? Attending school or childcare regularly? Playing and interacting? Spending extended periods alone in a pram, cot or in front of the television?

- Are they adequately supervised? Are there clear boundaries?

- Are parents spending time with the child and providing nurturing care?

- Are there regular routines?

- Is discipline appropriate and non-punitive?

- What is the relationship between siblings? (ibid)

Child’s mental health

- Is the child known to/engaged with mental health services?

- Are they engaging in self-harm/high risk activities (drug taking, sexualised behaviours, suicidal ideation, criminal activity)

- Do they have a social network?

- Are they/have they been bullied on social media or in school?

- Are there available supportive family, friends, or neighbours?

Gather information from networks

In addition to immediate family, it is beneficial to obtain information from other people and sources that are familiar with the child. This can include extended family (where appropriate) and professionals who have knowledge of the child and family. Seek advice from specialist practitioners and any adult services involved with the family.

Consider how the use of multidisciplinary assessments for children, such as occupational therapists, speech pathologists, paediatrician can add value to understanding a child’s needs and experiences and contribute to your assessments.

These informal and formal supports can provide valuable insights and be collaborative partners in decision-making and monitoring the progress towards change.

Consider the context

Gather information related to the context of the issue. Most commonly, the factors involved in child abuse and neglect are domestic violence, drug or alcohol misuse, and mental health issues (Bromfield et all 2010). Families can also experience housing and financial instability, social isolation and neighbourhood disadvantage. Parents may be dealing with their own experiences of trauma (ibid). Contextual considerations as they affect parenting might be (ACT Government 2019):

- Type of housing and housing security, for example, homelessness, share housing, overcrowding

- Financial or food insecurity

- Evidence of squalor and/or hoarding

- Are there vulnerable people living in the home?

- Are there known psychiatric, medical, or other risk factors (for example, domestic or family violence, substance use)?

- Are there cultural, language or communication barriers?

- Do family, friends, carers visit?

- Do unsafe people visit?

- Are formal services involved currently or historically?

- Are there neighbour disputes?

- Is animal hoarding a factor?

- How long have the factors persisted?

Practice Point

Being intentional and thoughtful in your interactions may help to build rapport with a child who may be scared or uncertain about disclosure or feeling torn between loyalty to their parent or carer. Try to communicate clearly what your role is and how the process will unfold and offer the child as much control as possible over their involvement (within the limits of their developmental ability). Where possible, give them options regarding the timing and order of events.

SHARE information and evidence

Clarify with families, children and professionals the accuracy of the information and evidence to ensure a full understanding of the risk and safety issues.

The sharing of information supports collaboration, allows services to identify needs and risks and verify that the child’s needs are being met.

Information sharing promotes timely intervention and supports integrated service delivery and processes.

Provisions in the Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017 (SA) support appropriate information sharing, as does the Information Sharing Guidelines (see SFS Information Sharing Paper).

SORT information and evidence (Victoria Government 2021)

Sort the information within the SFS Assessment document in relevant categories to assist with a structured approach to analysis.

This provides a map and a process for managing all the information gathered

This builds a picture of the situation and key information that can be matched against evidence-based (risk) factors.

STORE information and evidence (ibid)

Practitioners must be diligent, targeted and purposeful in the writing and recording of case notes.

Sound case notes support accurate risk assessment and analysis and are a record of all contacts and events in the intervention.

Case notes should be factual and objective (refer to SFS Record Keeping and Case Noting PG).

Sound case notes meet legislative, legal and organisational accountabilities.

Case notes can be subpoenaed and released in FOI investigations and other such legal settings.

Assessing for cumulative harm

This process of seeking, sharing, sorting and storing information and evidence, provides a solid basis for the following task of analysis. Practitioners evaluate the combined impact of multiple adverse experiences or stressors on a child and the impact on the child’s wellbeing and functioning. By looking at the interconnectedness of past and present experiences within context, the practitioner can better identify triggers, patterns and underlying factors contributing to the current situation. This involves identifying and understanding the various challenges, traumas and risks that have accumulated over time, as well as anticipating future stressors, if the situation remains unchanged.

Analysis helps the practitioner think about and bring together information and evidence gathered. Analysis involves examining and evaluating what is known in detail and studying the relationships and patterns within the information. It is a logical step that should allow the practitioner to draw some conclusions or offer a hypothesis. Practitioners are to:

- be mindful of not simply repeating or restating the facts (description)

- consider the impact on the child or young person (analysis)

- link the information and evidence to formal knowledge (interpretation) such as child development, reasoning skills and practice wisdom

- use this to inform professional judgement about risk to a child or young person (ACT Government 2019) (judgement).

In this process the practitioner is formulating a hypothesis (or opinion) on the likelihood of cumulative harm to the child. As new information is gathered, the hypothesis may change. Practitioners should keep an enquiring mind.

The information and the evidence are weighed up for significance in terms of each individual child’s experience. The definitions below will assist with this.

Information

Facts or data about a situation. The information may vary in terms of relevance, detail, and accuracy.

Direct evidence

Information that addresses the issue at hand. It is relevant and offers an answer to a specific question or hypothesis, although it may not provide a complete answer, or even an accurate one. An example may be a bruise on a child’s body or somebody who witnessed the abuse (Victoria Government 2021).

Indirect evidence

Suggests the existence or occurrence of a fact but does not directly prove it. It can seem relevant, especially if looking for patterns in the information and can support or weaken the direct evidence, but it carries no weight until it is combined with other evidence to arrive at a conclusion (Shown Mills 2009). Examples may be changes in a child’s behaviour or inconsistencies in a perpetrators story.

Negative evidence

The absence of what we would expect to happen in a certain situation. For example, if a guard dog is not barking during a robbery (ibid). An example might be, a child not flinching, recoiling, or displaying any reaction to a threat.

Four dimensions of analysis

To assist practitioners with making sense of the large amount of information collected, there are four dimensions of analysis that guide an assessment for the likelihood of cumulative harm.

Dimension 1– Vulnerability of the child

Dimension 2 – Severity of harm

Dimension 3 – Likelihood of harm

Dimension 4 – Safety.

Dimension 1 VULNERABILITY of the child (adapted from Victoria Government 2021)

This dimension focuses on the characteristics of each child or young person in relation to their susceptibility to harm. It includes the characteristics and capacity of the parents to meet the child’s needs and address issues of harm and safety.

Consider:

Who is the child in the context of family, culture and community? Link information and evidence with consideration of:

- Child

- Parent and caregiver

- Risk factors

- Family, community, and environment.

Individual child characteristics and needs, for example:

- Infant under 1 year or premature birth

- Age and developmental stage

- Severe disability, seizures

- Complex medical needs.

Parental/carer capacity to meet needs and address harm, for example:

- Mother and father have a disability that impacts on their capacity

- Recent admission of parent to hospital from substance use/overdose or poor mental health

- Multiple missed medical appointments for child/unaddressed need

- Inadequate supervision of child.

Child within the context of family and community, for example:

- Is DFV present in this situation?

- A child’s place in the sibling group may affect vulnerability

- Child’s relationship with parents/carers

- The child’s functioning at day care, school

- Increased vulnerability in different environments

- Risk taking behaviour in older children/youth

- Opportunity for harm

- Child’s exposure to the source of the harm.

Dimension 2 SEVERITY of harm (adapted from Victoria Government 2021)

This dimension focuses on the relationship between the specific vulnerabilities of the child and the type, degree or severity of harm experienced.

Consider:

What is the child or children’s experience of harm, past or current? Links information and evidence with consideration of:

- Child

- Harm

- Parent and caregiver

- Family violence.

Types of harm:

- Lower-level abuse and neglect is less visible- can have significant impact over time

- Significant risk factors consistent with domestic or family violence.

Pattern, history and accumulation (cumulative harm):

- Indicators that harm is escalating, chronic or episodic

- Consider potential long-term effects.

Clinical Judgement: Consequence or impact on the child

Dimensions 1 and 2- are important because the vulnerability of the child and the severity of harm come together to make a judgement about the consequence or impact on the child, which can be categorised as:

- Severe

- Significant

- Concerning

- Insufficient evidence.

Severe

The impact of harm has been determined by a professional to be permanent (for example, shaken baby syndrome).

The harm will have a permanent effect on the child’s development (for example, injuries to a baby that will become evident over time).

Harm has been endured over a long period of time (for example, failure to thrive).

The harm is a result of an acute episode (for example, assault of a child) (Victoria Government 2021).

Significant

The impact of harm has been determined by a professional to be detrimental to a child’s development and functioning (for example, chronic neglect requiring significant therapy to reach developmental milestones).

The impact of the harm will have repercussions in the short and medium term (for example, children missing large amounts of schooling).

The impact of the harm will likely have detrimental impact on the child’s development (for example, exposure to drugs and alcohol in utero) (ibid).

Concerning

The impact of harm is isolated (for example, unsupervised child due to communication breakdown between parents).

The parents have taken immediate action to address the harm (for example, child exposed to parent’s substance abuse behaviours but parents have taken (verifiable) steps to secure treatment and support.

The impact of harm is unlikely to have long term effect (for example, a child smacked on the bottom with open hand because they had run onto the road, had occurred only once and is not the usual parenting practice) (ibid).

Insufficient evidence

After following up it is determined that the child and family may benefit from universal services to better support parenting, general functioning and community connections.

Dimension 3 LIKELIHOOD of harm (adapted from Victoria Government 2021)

This dimension looks at the factors that increase the likelihood that harm has occurred, is currently occurring or may be likely to occur in the future. Practitioners focus on the behaviours, abilities, attitudes and beliefs about harm and the contributing factors of the significant adults in the child’s life.

Consider:

What are the parental or carer characteristics associated with occurrences or the recurrence of harm? Links information and evidence with consideration of:

- Harm

- Parent and caregiver

- Family violence

- Family, community and environment.

Prior pattern of behaviour and attitude towards child, for example,

- Past behaviour as a predictor of future behaviour

- Number of times/recency and severity of harm

- Have previous interventions decreased risk/increased safety?

Attitudes and beliefs of the parents/carers about harm causing behaviours, for example,

- Carers who are disbelieving or not able to acknowledge or address concerning issues

- Beliefs by parent or carer the (harmful) behaviour is justified- or the child is to blame, increases risk.

Contributing factors, for example,

- Multiple issues such as parent or carer substance abuse, poor mental health

- Domestic or family violence, financial hardship

- Unmet medical and/or developmental needs

- Persisting and cumulative concerns at a lower-level increase likelihood of cumulative harm

- Squalor and hoarding as environmental concerns.

Practice point

If during your assessment you develop concerns about the immediate safety of a child, you should contact CARL 131478 and SAPOL 131444 and follow risk management processes.

Dimension 4 SAFETY (includes protective factors) (Victoria Government 2021)

This dimension looks at the way strengths and factors of protection and safety can contribute to a decrease in the probability of harm occurring or recurring.

Consider:

What are the factors present for the child and family that decrease the probability of harm and provide protection for the child or young person?

- Link information and evidence with consideration of:

- Harm

- Strengths

- Protection and safety.

Factors of protection and safety are to be checked and verified to ensure risk is being managed.

Strengths

Considers child, parental, kinship and cultural and community strengths.

- Strengths are positive aspects or attributes of the child, family, community and environment, but do not necessarily reduce risk of harm

- A strength may be an indicator of change, for example a perpetrator commencing counselling for DFV indicates motivation to change, but is not protective without other measures

- Strengths positively impact upon a child’s experience, but are not necessarily protective.

Protection

Protection is factors that moderate or mitigate the likelihood of harm.

- Protection is an action focussed activity that is demonstrated

- Evidence of actions that reduce or stop exposure to harm

- Consider whether the protective measures extend to all siblings.

Safety

Current and future focussed.

- Safety is strengths demonstrated as protective measures, over time

- Safety factors are directly linked to specific concerns

- May be present outside of parental care- for example, safety plan for children to stay with grandparents.

Families may have multiple strengths, but they may not be enough to provide protection and mitigate risk. However, these strengths can be building blocks to create safety in the future.

- Remember that a parents’ desire to change harmful or neglectful behaviours does not always equal capacity to change

- Be mindful of the urgency of the child’s timeframes for safety, attachment needs and relationships

- Consider the recency, severity and frequency of the parent’s behaviour. In the absence of effective intervention, these could be expected to continue

- Consider the context of issues (such as mental health, DFV) and the extent to which these singularly or collectively reduce the capacity of the parent to provide safety and care (Victoria Government 2021)

- For further information on safety, Refer to SFS Safety Planning Practice Guide

Clinical Judgement: Probability of harm

Dimension 3- Likelihood of Harm and Dimension 4- Safety are important because they come together to make a judgement about the probability of harm, which can be categorised as:

- Very likely

- Likely

- Unlikely.

The practitioner makes this assessment based upon the factors that either increase or decrease the likelihood of harm. Likelihood is about increase in harm and safety is about decrease. Probability is weighing up increase and decrease to make an overall judgement. Probability of harm is guided by:

Very likely

- Factors of likelihood of harm significantly outweigh factors of safety

- There are no identifiable factors of safety

- Previously confirmed harm- with no identifiable or sustained carer/parent change in behaviour

- The threshold for unacceptable risk is reached, indicating immediate safety concerns and intervention (Victoria Government 2021).

Likely

- Protective factors exist but are not yet tested or demonstrated over a period of time to reduce risk

- A pattern of cumulative harm has been identified

- A pattern of increasing or escalating harm has been identified

- The balance of probabilities suggests that harm is more likely than not (ibid).

Unlikely

- Risk issues exist, but at a lower level that does not warrant statutory intervention-but intervention with supports would be of benefit

- There are protective factors, demonstrated over time to address risk factors

- Risk issues have been identified at a lower level and parents/carers have taken action to address

- It is not impossible, but unlikely harm will occur or recur (ibid).

Determining cumulative harm

The practitioner then considers the Consequence of Harm (Dimensions 1 and 2) and the Likelihood of Harm (dimensions 3 and 4) and can make judgements in relation to the presence and level of cumulative harm.

Clinical judgement is the ability to make considered decisions or arrive at reasonable conclusions or opinions, based on available evidence (Oxford Online Dictionary).

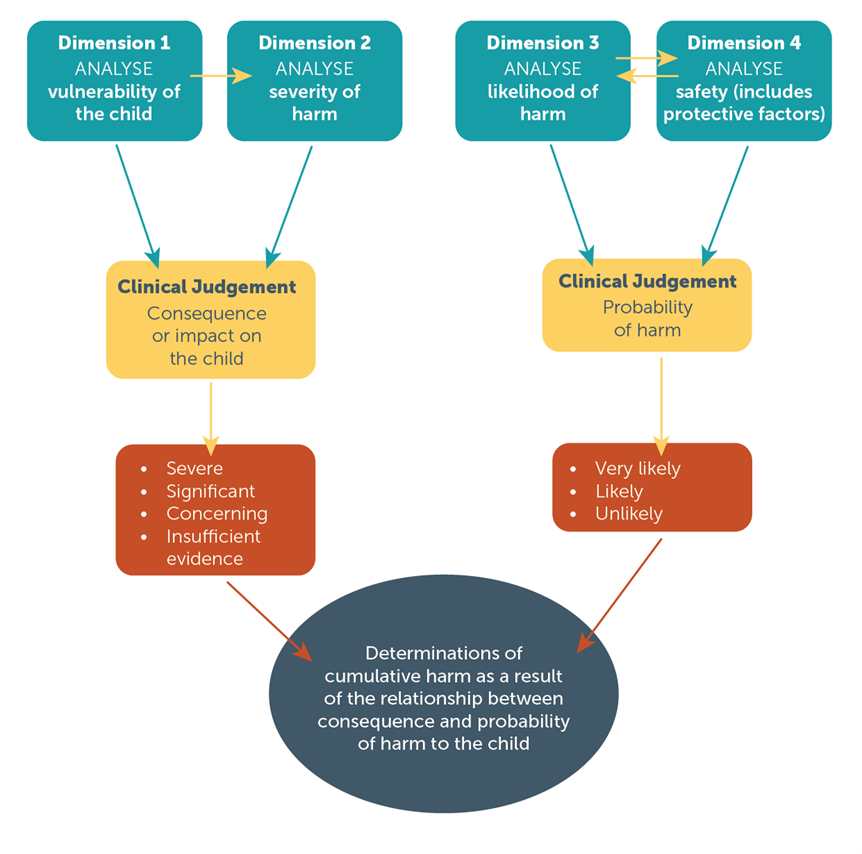

This flowchart illustrates the process:

Plain text flowchart description

A flowchart shows how the Dimensions inform decision making to determine cumulative harm.

Dimension 1 'Vulnerability of the child' and Dimension 2 'Severity of harm' are considered. Clinical judgement then determines the consequence or impact on the child. The consequence is rated as severe, significant, concerning or insufficient evidence.

Dimension 3 'Likelihood of harm' and Dimension 4 'Safety (and protective factors)' are considered together. Clinical judgement then determines probability of harm. The probability is rated as very likely, likely or unlikely.

These considerations result in a determination of cumulative harm as a result of the relationship between consequence and probability of harm to the child.

Management of cumulative harm

The process of gathering, assessing and analysing information to identify cumulative harm, requires a comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach. The analysis must present the current situation and context, with the outcomes for the child if their circumstances remain the same.

A considered assessment and analysis of cumulative harm provides:

- a formulation of what needs to change to increase safety for the child/young person

- an evidence base on which to make decisions and take action

- a platform for future planning and interventions

- a framework for managing and reducing risk

- a framework against which progress and changes can be measured.

This thoughtful approach centred on children and families, helps practitioners to navigate the challenges of addressing cumulative harm within the case management process.

When these results are considered against the SFS (IFS Case Management) Child Safety Risk Rating and recorded on the SFS Assessment Form they provide a clear representation of the identified risks, enabling practitioners and supervisors to know, understand and be able to articulate the type and level of risk related to the families they work with. The assigned rating provides the practitioner with a range of actions related to risk that are regarded as essential components of best practice, case management.

Case Management

The SFS case management process offers a structured and coordinated approach by developing tailored intervention plans and providing coordinated support to address safety concerns, and the factors contributing to cumulative harm. The systematic nature of case management enables ongoing monitoring, evaluation and adjustment of interventions to meet the evolving needs of children and families. Through a collaborative and comprehensive approach, practitioners can work towards establishing a supportive and nurturing environment that promotes safety, positive outcomes and resilience for children and families.

SFS resources that are available to SFS practitioners in their management of cumulative harm, are listed in the next section.

Reflective Practice and consultation

Supervision

An assessment and analysis of harm and cumulative harm is informed by the development of ongoing professional knowledge. Practitioners use clinical supervision to discuss risk situations, reflect on and question their judgement, test hypotheses and be open to new information and ongoing improvement in their practice. This may include consulting with and mentoring from supervisors, cultural consultants, clinical leads and other professionals and experts to support decision making.

Depending on the issues or factors being analysed, consider what professional knowledge you hold, and what professional knowledge needs to be sought to better inform the process. For example, a risk assessment relating to neglect of an infant would benefit from professional knowledge concerning early childhood development or specialised infant mental health.

For further information, practitioners should refer to the SFS Clinical Supervision Practice Guide

Consultation

Consultation with the Clinical Practice Team, the Aboriginal Practice Team and the Disability Consultant ensures the consideration of complexity, cultural responsiveness, intersectionality and experiences of disability that impact the experience of trauma and the presence or accumulation of harm. Consultation should be utilised frequently to support best practice and to assist with the management of risk.

Consultation supports practitioners to determine the level of risk and the most appropriate approach to risk management and safety planning. In this process the practitioner builds their knowledge base for practice, improves working relationships in and across organisations and as a result provides the best possible response to children and families. For further information, practitioners should refer to the SFS Consultation Practice Guide

Practice guidance and resources

Case management

SFS Case Management Framework

SFS Aboriginal Cultural Practice Framework

SFS Safety Planning Guide

SFS Consultation Practice Guide

SFS Assertive Engagement Practice Guide

SFS Clinical Supervision Practice Guide

SFS Record Keeping and Case Noting Practice Guide.

Risk and Escalations

SFS High Risk Alert Practice Guide

SFS Risk and Escalations Practice Guide SFS Conflict of Interest.

Multi-agency responses

SFS Responding to DFV Practice Guide

SA Health Foot in the Door

SFS Information Sharing Practice Paper.

Information Sharing Guidelines

Child and Family Health Service (CaFHS) universal health checks – DHS/DCP referral pathway.

Escalations

SFS Risk and Escalation Practice Guide

SFS High Risk Alert Practice Guide.

Bibliography

- Australian Capital Territory Government, 2019 Working with families affected by cumulative harm or neglect, Supporting good practice, Child and Youth Protective Services

- Australian Childhood Maltreatment Study (2023) https://www.acms.au/

- Australian Institute of Family Studies 2014, Effects of child abuse and neglect for children and adolescents. Melbourne, Victoria http://www.aifs.gov.au/cfca/pubs/factsheets/a146141/index.html

- Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020 Child protection and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, Policy and practice paper. Online resource Child protection and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children | Australian Institute of Family Studies (aifs.gov.au)

- Bromfield,L,. Lamont,A., Parker,R., and Horsfall, B 2010 Issues for the safety and wellbeing of children in families with multiple and complex problems. National Child Protection Clearinghouse No.33 2010

- Bryce, I. 2018, Australian Institute of Family Studies A Review of cumulative harm: A comparison of international child protection practices. Children Australia, 43 (1), 23-31

- Bryce, I.; Collier, S. 2022 A Systematic Literature Review of the Contribution Accumulation Makes to Psychological and Physical Trauma Sustained through Childhood Maltreatment. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 307–329. Online resource: https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare2020026

- Catholic Healthcare 2021, Effective service responses Hoarding and Squalor: An educational package for The Office of Local Government, Participant workbook. Online resource Hoarding and Squalor Workbook (nsw.gov.au)

- Catholic Healthcare Services Hoarding and Squalor Handy Tools Resources and tools (catholichealthcare.com.au)

- Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017 (SA). Government of South Australia Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017 | South Australian Legislation

- Eppingstall, J., Stuffology, Hoarding + Neglect: Child Protection, in service training provided to Safer Family Services May 2023

- Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., Tolin, D. F., & Renaud, S. (2008). Development and validation of the clutter image rating.Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 30(3), 193–203.Online resource: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10862-007-9068-7

- https://www.catholichealthcare.com.au/globalassets/hoarding--squalor/hs-downloads/210902-chl-clutter-image-rating-scale---update.pdf

- Government of South Australia. Child Death and Serious Injury Review Committee 2022, Review Summary: A review into 13 cases of severe domestic squalor Online resource: Child Deaths South Australia 2005–2022 (cdsirc.sa.gov.au)

- Hervatin, M. 2020 Practical strategies for engaging children in a practice setting, parenting Research Centre Australia. Retrieved from https://emergingminds.com.au/resources/practical-strategies-for-engaging-children-in-a-practice-setting

- Higgins, D.J., Matthews, B., Pacella, R., Scott, J.G., Finkelhor, D., Meinck, F., Erskine, H. E., Thomas, H. J., Lawrence, D. M., Haslam, D. M., Malacova, E., Dunne, M. P., (2023). The prevalence and nature of multi-type child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study; The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 218 No. 6, pp. S19-S24.’

- Oxford online dictionary https://www.oed.com

- Say it out loud, https://sayitoutloud.org.au/professionals/key-messages/?state=SA

- Sheehan, R. 2019. Cumulative harm in the child protection system: The Australian context. Child and Family Social work, 24 (4), 421-429

- Shown Mills E., 2009 Evidence explained: Citing history sources from artefacts to cyberspace, Genealogical Publishing Company, USA

- South Australian Department for Health and Ageing, SA Health 2013, A foot in the door: stepping towards solutions to resolve incidents of severe domestic squalor in South Australia. Health Protection Programs Hoarding Guideline_FINAL_23_Aug_13 (sahealth.sa.gov.au)

- United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Victorian State Government Cumulative Harm, Best interests case practice model, Specialist Practice Resource 2012. Online resource Cumulative harm specialist practice resource (cpmanual.vic.gov.au)

- Victorian State Government, Families Fairness and Housing, SAFER children framework guide: the five activities of risk assessment in child protection 2021. Online resource SAFER children framework guide October 2021.pdf (cpmanual.vic.gov.au)

- United Nations 1989 United Nations Human Rights Convention on the rights of the child-

- Victorian State Government Department of Human Services, 2012 Best interest case practice model: Summary Guide Department of Families Fairness and Housing Victoria | Best interests case practice model - summary guide (dffh.vic.gov.au)

- World Health Organisation 2022 Child Maltreatment: fact sheet. Online resource: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment